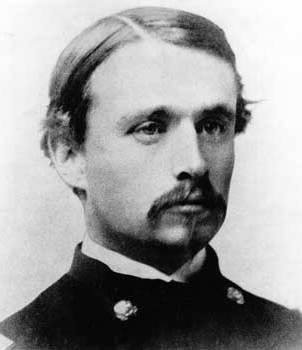

Governor Andrew decided to offer the colonelcy of the 54th to (then) Captain R.G. Shaw, and wrote to Shaw’s father to enlist his aid in convincing Shaw to accept the commision; this is followed by the Governor’s letter to Shaw himself:

BOSTON, Jan. 30, 1863.

FRANCIS G. SHAW, Esq., Staten Island, N. Y.

DEAR SIR,

—As you may have seen by the newspapers, I am about to raise a colored regiment in Massachusetts. This I cannot but regard as perhaps the most important corps to be organized during the whole war, in view of what must be the composition of our new levies ; and therefore I am very anxious to organize it judiciously, in order that it may be a model for all future colored regiments. I am desirous to have for its officers — particularly for its field-officers — young men of military experience, of firm antislavery principles, ambitious, superior to a vulgar contempt for color, and having faith in the capacity of colored men for military service. Such officers must necessarily be gentlemen of the highest tone and honor; and I shall look for them in those circles of educated antislavery society which, next to the colored race itself, have the greatest interest in this experiment.

Reviewing the young men of the character I have described, now in the Massachusetts service, it occurs to me to offer the colonelcy to your son, Captain Shaw, of the Second Massachusetts Infantry, and the lieutenant-colonelcy to Captain Hallowell of the Twentieth Massachusetts Infantry, the son of Mr. Morris L. Hallowell of Philadelphia. With my deep conviction of the importance of this undertaking, in view of the fact that it will be the first colored regiment to be raised in the free States, and that its success or its failure will go far to elevate or depress the estimation in which the character of the colored Americans will be held throughout the world, the command of such a regiment seems to me to be a high object of ambition for any officer. How much your son may have reflected upon such a subject I do not know, nor have I any information of his disposition for such a task except what I have derived from his general character and reputation; nor should I wish him to undertake it unless he could enter upon it with a full sense of its importance, with an earnest determination for its success, and with the assent and sympathy and support of the opinions of his immediate family. I therefore enclose you the letter in which I make him the offer of this commission; and I will be obliged to you if you will forward it to him, accompanying it with any expression to him of your own views, and if you will also write to me upon the subject.

My mind is drawn towards Captain Shaw by many considerations. I am sure he would attract the support, sympathy, and active co-operation of many among his immediate family relatives. The more ardent, faithful, and true Republicans and friends of liberty would recognize in him a scion from a tree whose fruit and leaves have always contributed to the strength and healing of our generation. So it is with Captain Hallowell. His father is a Quaker gentleman of Philadelphia, two of whose sons are officers in our army, and another is a merchant in Boston. Their house in Philadelphia is a hospital and home for Massachusetts officers; and the family are full of good works; and he was the adviser and confidant of our soldiery when sick or on duty in that city. I need not add that young Captain Hallowell is a gallant and fine fellow, true as steel to the cause of humanity, as well as to the flag of the country.

I wish to engage the field-officers, and then get their aid in selecting those of the line. I have offers from Oliver T. Beard of Brooklyn, N. Y., late Lieutenant-Colonel of the Forty-eighth New York Volunteers, who says he can already furnish six hundred men; and from others wishing to furnish men from New York and from Connecticut; but I do not wish to start the regiment under a stranger to Massachusetts. If in any way, by suggestion or otherwise, you can aid the purpose which is the burden of this letter, I shall receive your co-operation with the heartiest gratitude.  I do not wish the office to go begging; and if the offer is refused, 1 would prefer it being kept reasonably private.

Hoping to hear from you immediately on receiving this letter,

I am, with high regard,

Your obedient servant and friend,

JOHN A. ANDREW.

( From [BBR,pp.3-5])

Captain,

I am about to organize in Massachusetts a Colored Regiment as part of the volunteer quota of this State – the commissioned officers to be white men. I have today written your Father expressing to him my sense of the importance of this undertaking, and requesting him to forward to you this letter, in which I offer to you the commission of Colonel over it. The Lieutenant Colonelcy I have offerred to Captain Hallowell of the Twentieth Massachusetts Regiment. It is important to the organization of this regiment that I should receive your reply to this offer at the earliest day consistent with your ability to arrive at a deliberate conclusion on the subject.

Respectfully and very truly yours,

John A. Andrew(From [BCF], p.23)