Boston [BCF]

Feb. 18,1863Dear Father,

Will you please inquire of Judge Emerson where his son Charles is to be found, and whether he would take a First Lieutenancy in the coloured regiment. I liked what I saw of him at college very much, and am very anxious to get hold of him. I am occupied all the time. Things look very encouraging.

Love to Mother.Affectionately, your son,

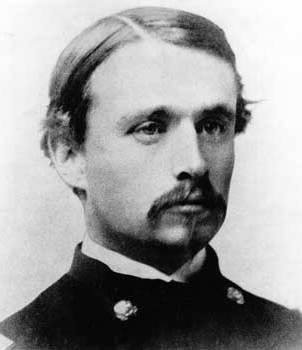

Robert G. Shaw

February 18,1863 [BCF]

My Dear Annie,

Yours of Monday I received this morning. . ..

Last night I was at Milton Hill.Miss Sedgwick (Aunt Kitty) came over. She talked about you, and told me how much she loved your mother, and you and Clem. I thought him a very charming person. Cousin Sarah was very kind and sympathizing; she wants to see you very much, and you will have to come here some time. I have not seen Aunt Cora, as she was ill when I went there.

Do write to me often, Annie dear, for I need a word occasionally from those whom I love, to keep up my courage. Whatever you write about, your letters always make me feel well; and I have enough discouraging work before me to make me feel gloomy.

Always, with great love,

Yours,

Rob